Writer and lay teacher Sallie Jiko Tisdale is recovering a lineage of female Buddhist ancestors.

There are practical problems not easily resolved in creating a line for chanting. In many cases the women are commonly known by only a single name, while with men we often know the family, temple, regional, and given names as well as dharmic and posthumous titles. It is rather difficult to chant a list of names of widely varying lengths, and for a while we tried dropping a second name in some cases for rhythmic ease. But this is one of the ways a woman’s story can slowly disappear when what we know of her is already skeletal. We would appreciate receiving any new or corrected information about the women, including the spelling or variations of their names.

I’ve found Chinese women’s names spelled in a variety of ways. To change the spelling to ease pronunciation could also bury a woman’s history when little enough is known already. We recite Chinese names in Pinyin with Wade-Giles in parentheses to cover both possibilities, though spellings in historical material still vary.

Hyphens between syllables are used in our chanting version, along with dialetical marks such as macrons; they are eliminated here.

In bringing forth women’s history, one always faces the problem of terms. It has always been my inclination not to use gender-specific words, like bhikkuni, nun, abbess and so on. I’m concerned that as long as there are priests on one hand and female priests on the other, women will not be seen as holding an equal place. At the same time, I want us to remember the struggles that are specific to women. Some women favor such terms as bhikkuni and the Japanese suffix ni, which specifies female, precisely because without such markers, we can lose track of this unique history. We have chosen to give the women the same honorific as the men: dai-osho, « great priest. »

The offertory at the end was written by my teacher, Kyogen Carlson.

————————————————————————

The Women’s Lineage

The Mythical Ancestors

Prajna Paramita

The Mother of the Buddhas; the Womb of the Buddhas. Wisdom is often presented as a female principle; this goddess represents both the great Wisdom Goddess as a deity and the Prajnaparamita Sutra itself.

Maha Maya

The mother of Shakyamuni; she died a week after his birth and became a supernatural figure. She is represented as a Bodhisattva in the Avatamsaka (Flower Ornament) Sutra, where she represents non-abiding and non-attachment, existing in a realm « unobstructed like space. »

Ratnavati

A girl described in the Ocean Dragon King Sutra. She engages Mahakasyapa in a mondo on whether or not women can be fully enlightened. She convinces him there is no difference between men and women, and Shakyamuni Buddha predicts her supreme enlightenment to come.

Shrimala (or Srimala)

A female lay bodhisattva contemporary with Shakyamuni described in the sutra The Lion’s Roar of Queen Shrimala. She is the female equivalent of Vimalakirti as an example of enlightened practice in lay life..

The Indian Ancestors

Maha Pajapati

Shakyamuni’s aunt and stepmother. She is the one who challenged the ban on women becoming monks in Shakyamuni’s original Sangha. She became the first female monk and leader of the female monastic community. She is said to have lived to 120 years.

Khema

She was known as « Khema of Great Wisdom » because she grasped the Buddha’s entire teaching on first hearing it as a laywoman. She helped run the women’s monastic order and is called the most exemplary female monk in the Pali Canon.

Pata-cara (or Pata Chara)

She went mad from grief after her children, parents and husband died and wandered the countryside. Eventually she met the Buddha, who calmly told her to recover her « presence of mind, » and she was cured. She became a highly influential teacher who brought many women to the Dharma and had many disciples.

Ut-tama

One of Pata-cara’s major disciples, she exemplifies the ability to overcome psychological confusion to attain enlightenment. She was devoted to the idea that hearing the Dharma for even a brief time was enough if you heard it clearly.

Bhadda (or Bhadda Kundalakesa)

Bhadda was a Jain at the time of Shakyamuni. She was a highly intelligent woman and felt dissatisfied by the lack of intellectual stimulation among the Jains, who seemed disinclined to struggle with their understanding of the truth. She did Dharma combat with Sariputra and was praised by the community for her rapid thought and great understanding.. She is the only woman ordained directly by Shakyamuni in front of the whole Order. « ‘Come, Bhadda,’ he said to me; that was my ordination. »

Dhamma-dinna

She lived at the time of the Buddha but it was said of her that she had lived and trained with many Buddhas through many lifetimes, and even helped one Buddha rise from a deathbed. In Shakyamuni’s time, her husband went to hear the Buddha preach and decided to become a monk. He told Dhamma-dinna to do whatever she wanted. She asked to be admitted to the nuns’ order and entered solitary practice. Because of her past lives of merit, she quickly realized Arhatship and returned to the nuns. She « answered every question as one might cut a lotus-stalk with a knife, » and the Buddha called her the foremost woman preacher, and her words were declared to be buddhavacana, Buddha words. She converted many people and became the master of many disciples and heirs

Kisagotami

Kisagotami was a cousin of Shakyamuni. She was overcome with grief when her child died, and carried his dead body for days. The Buddha told her that he would revive her son if she brought him a mustard seed from a house where no one had died. She went from house to house seeking this, but was unable to find a family untouched by death. With this understanding, her mind was healed. She became a nun and was eventually known as foremost in austerity.

Dhamma

Dhamma’s husband refused to give her permission to ordain as a nun, so she waited without complaint until he died. She then ordained, as a weak, old woman, and was enlightened when she tripped and fell due to her frailty. She was known as foremost in the keeping of the form.

Suk-ka

Dhammadinna’s heir and also a great preacher and leader with hundreds of followers. She is said to have lived for many centuries and practiced with many Buddhas. She converted to Shakyamuni’s teaching as a young girl, but she wasn’t able to awaken completely until she met her true teacher in human (and female) form.

Ub-biri

She also lived for centuries with Buddhas and accumulated great merit. After her beloved daughter died, she could not stop mourning until the Buddha pointed at the graveyard and said it was full of his daughters. On seeing the universal nature of suffering, she became an arhat while still a laywoman.

Uppalavanna

This nun was the woman foremost in magical power and was able to perform miracles. She was so beautiful that men fought for her hand in marriage, and finally her husband asked her to ordain in order to spare him the decision of who should be her husband. She was raped by an angry suitor after her ordination. It is because of this event that women were denied the right to do solitary forest practice and extra rules were added to the women’s vinaya, but she expressed only joy and never anger. (She may be conflated with Utpalavarna below.)

Sumana

She was the lay disciple most eminent in Shakyamuni’s time. She could not be ordained because she had to care for her grandmother, but made an effort to attend the Buddha’s lectures whenever he was near.. She was an old woman herself before her grandmother died. At that time, she and her brother were ordained together and shortly after that, she achieved awakening.

Punnika

She was a slave, a water-carrier. She became a ‘stream-entrant’ after hearing one of the Buddha’s discourses. She asked for ordination, impossible for slaves, but with Shakyamuni’s intercession, she was later freed and became a monk. She was also adopted by her former owner. Her experiences doing zazen in all conditions allowed her to awaken.

Subha

Subha was walking in the forest when she was attacked by a rapist. She engaged him in a mondo about the falsehood of physical beauty and then plucked out her own eye in order to demonstrate impermanence.. The rapist apologized and released her. Shakyamuni later magically restored her eyesight.

Utpalavarna

In a past life, she was a prostitute who put on monk’s robes as a joke. The Buddha of that time predicted her future Buddhahood from the merit of that act alone. Her story is told in the Jataka sutra and used by Dogen in his chapter « Kesa Kudoku, » on the miraculous merit of the robe. As an arhat contemporary with Shakyamuni, she was said to be able to perform miracles.

The Chinese Ancestors

Zongchi (Tsung-ch’ih)

She was the daughter of an Emperor of the Liang dynasty of 6th-century China. She became Bodhidharma’s disciple. In Dogen’s Shobogenzo chapter called Katto (« Twining Vines »), she is named as one of his four Dharma heirs. Although Bodhidharma’s line continued through another of the four, Dogen emphasizes that each of them had a complete understanding of the teaching. (She is also known as Ts’ung-ch’ih, by her title, Soji, and as Myoren, her nun name.) [early-mid 500s]

Shih-chi (Shi-ji)

Her story is in the « Ancestor’s Hall Collection » of awakening stories. In one instance, she arrived at a temple and didn’t remove her hat, as etiquette required. She told the head monk she would remove it only if he could say « something » (worth hearing, that is). He cannot, so she leaves, and he is laughed at as a fool by fellow monks. This stimulates him to find a true teacher and throw himself into real practice. [500-600s]

Ling Hsing-p’o (Ling Xing-po)

She is listed only as a footnote in the transmission story of a male teacher in the Ching-te-ch’uan-teng-lu Collection of 1008. Her accomplishment and lectures form the bulk of his story, as she defeated and taught him. [600-800s]

Ling-chao (Ling-zhao)

She was Layman Pang’s daughter. For most of her life, she traveled with him in poverty, seeking teaching and doing cave meditation. She is the model for Fishbasket Guanyin and much admired for the simplicity and confidence of her practice. [800s]

Liu Tiemo (Iron Grinder Liu)

Known everywhere as « Iron Grinder Liu, » she was an eccentric and fearless teacher famous for « grinding up » the delusions in everyone with whom she engaged in Dharma combat. [800s?]

Mo-shan Liao-jan (Liao-ran)

Mo-shan, which means Summit Mountain, was well known in her time (around 800 A.D.) and referred to by many later writers. She is one of the role models of wisdom cited by Dogen in his chapter Raihai-tokuzui (« Paying Homage and Acquiring the Essence »). Mo-shan was a disciple of Kao-an Ta-yu and is the first woman Dharma heir in the official Ch’an transmission line. Mo-shan has a chapter in the Chinese book of enlightenment stories called the Ching-te-ch’uan-teng-lu, the « Record of the Transmission of the Flame, » from 1004 A.D.

Mo-shan is the first recorded woman who was the teacher of a man. Dogen notes that Chih-hsien’s willingness to overcome his cultural resistance to being taught by a woman was a sign of the depth of his desire to attain understanding. In Japanese, her name is spelled Matsuzan.. [800-900]

Miao-hsin (Miao-xin)

Her story is told in one of the Chinese transmission histories and used as a prominent example in Dogen’s chapter, Raihai-tokuzui, « Paying Homage and Acquiring the Essence. » Miao-hsin was a disciple of Yung-shan Hui Chi, who said of the resistance to her gender, « Because a person who has attained the Dharma is an authentic ancient Buddha, we should not greet that person in terms of what she once was. When she sees me, she receives me from an entirely new standpoint; when I see her, my reception of her is based entirely on today… A nun who has received the treasury of the true Dharma eye through transmission… should receive the obeisance » even of Pratyekabuddhas, Arhats and advanced Bodhisattvas.

Miao-hsin was the provisions manager of the monastery. Seventeen visiting monks came to the monastery one evening and she overheard them arguing about a story in the Platform Sutra, concerning a flag in the wind – does the wind move or the flag? The monks requested formal teaching. She said, « It is not the wind which moves, it is not the flag which moves, and it is not the mind which moves. » With this they had a realization and became her disciples. Adds Dogen, « There is no doubt that there are many who will not pay homage to women or nuns, even if they have acquired the Dharma and transmitted it. They do not understand the Dharma, and since they do not study the Dharma, they are like animals. »

[mid-late 800s]

Wu-chin-tsang (Wu-jin Cang)

This nun was the aunt of a Confucian scholar. He sheltered Hui neng after his transmission, while he was in hiding and still a layman. While he stayed there, Wu-chin frequently recited the Parinirvana Sutra to him. His answers and explanations of the Sutra impressed her deeply, and she convince the villagers to rebuild a ruined temple and ask Hui neng to stay there. Eventually this became a famous monastery.

Tao-shen (Dao-shen)

She was a Dharma heir of Fu-jung Tao-k’ai (Fuyo Dokai), a master who helped revive the Soto line in China when it had declined. She had two heirs of her own but her lineage was broken after that. [late 1000s-early 1100s]

Hui-kuang (Hui-guang)

She was Abbess of Tung-ching Miao-hui-ssu, an important large convent and heir of K’u-mu Fa-ch’eng. She wore a purple robe given by the Emperor, from whom she received her Dharma name. Her story is recorded in the P’u-teng Collection and her sermons were also recorded. She taught in public to mixed assemblies of male and female monks and preached to the Emperor. [early-mid 1100s]

K’ung-shih Tao-jen (Gong-shi Dao-ren)

She was the heir of Ssu-hsin Wa-hsin, a nun, teacher, and poet. She wrote the « Record on Clarifying the Mind, » which was circulated throughout the country. She was well-married but left her husband, and asked her parents to allow her to be ordained, but they refused. After that, she practiced in solitude. She was awakened after reading Tu-shun’s « Contemplation of the Dharmadhatu. » After her parents’ death, she ran a bathhouse and wrote Dharma-challenge poetry on the walls to engage her customers in mondo. She became a nun in old age. [early-mid 1100s]

Yu Tao-p’o (Yu Dao-po)

She was the only Dharma heir of Lang-ya Yung-ch’i and apparently remained a laywoman. She was awakened upon hearing the teaching of « the true man of no rank. » After she bested the master and abbot Yuan-wu, he recognized her accomplishment and she was sought out by many monks for mondo and teaching. [early-mid 1100s]

Hui-wen

A teacher whose sermons were recorded. Her story is told in both the Lien-teng and Wu-teng Collections. [mid 1100s]

Fa-teng (Fa-deng)

Hui-wen’s Dharma heir; her sermons were recorded and her story is told in the transmission collections. [mid-late 1100s]

Wen-chao (Wen-zhao)

She became a nun at the age of seventeen and wandered in search of teachers. Eventually she became abbot of five different convents as a reformer of the Vinaya tradition to Ch’an. She had a male heir. Her story is recorded in the P’u-teng Collection where her sermons were recorded. She wore a purple robe given by the emperor. [late 1100s]

Miao-tao (Miao-tao)

She was an important teacher with many recorded sermons and records and a Dharma heir of Ta-hui Tsung-kao. Her story is presented in the Lien-teng Collection. She received Imperial approval to be a teacher and abbot. Her teaching was partly about the limits and necessity of teaching with words. She defeated the head monk at Kinzan Mountain in mondo by showing him the depth of his fear of and desire for her and other women. She was invited to « ascend the Hall » of the monastery which sponsored her convent and teach the monks there, the only certain record of this happening. (However, Dogen wrote that this happened a number of time with women masters.) Also known as Mujaku. [1089-1168?]

The Japanese Ancestors

Zenshin

She was ordained in 584, the first Japanese of either gender to be ordained as a Buddhist monk. In 588, she traveled to Korea for monastic training and eventually established a thriving female order in Japan. [late 500s]

Zenzo

Ezen

The second and third Buddhist monks in Japan, both were ordained shortly after Zenshin and trained with her, helping to establish Buddhism in Japan. [late 500s]

Komyo

She was an Empress and the first member of the Imperial family to be ordained as a Buddhist. She « profoundly shaped the contours of Buddhism in ancient Japan. » At her urging, the Emperor established National temples for men and women and the Sodo/Ni-sodo system was begun. She also copied sutras and altogether made « monumental contributions. » [Arai] [701-760]

Eshin

Shogaku

Disciples of Dogen in his early teaching years. Shogaku was a distant relative of his and an aristocrat who donated land and money to help build Kosho-ji.

Ryonen

She was one of Dogen’s main disciples, though ordained elsewhere, and her high understanding was noted in writings of other masters. Dogen wrote an exhortation specially for her and mentioned her accomplishment in a Dharma talk and in the Eihei Koroku. She was an old woman before her ordination and died before he did. [early 1200s]

Egi

She was ordained as a Daruma-shu nun, but became a disciple of Dogen’s at Eihei-ji. She spent more then twenty years with him and attended his sickbed. She also helped Koun Ejo in the transitional politics following Dogen’s death. There is an indication that she helped to record the Zuimonki. [early 1200s]

Joa

She was a disciple and heir of Giin, who was a disciple of Koun Ejo. She was given the practice of venerating and copying the Lotus Sutra. [late 1200s]

Mugai Nyodai

She is considered one of the most important women in all of Rinzai Zen. She was heir to Mugaku Sogen, the founder of Engaku-ji.. After her transmission, she established a temple known as Keiai-ji, the first sodo for women in Japan. She is also known as Chiyono (of the empty bucket). [1223-1298]

Ekan

She was the mother of Keizan and in her time became abbot of a Soto convent called Joju-ji. She was a great believer in miracles made possible through devotion to Kanzeon. Keizan praised her for unfailingly teaching Dharma to women. Her influence led to his vow to help all the women of « the three worlds and the ten directions » in her memory. [1200s-early 1300s]

En’i

En’i is mentioned in Keizan’s Doyaki, where he encourages monthly ceremonials in her honor « in perpetuity. » She donated large pieces of land to support the community.

Shido

The founder of Tokei-ji and a fully authorized teacher. Her mondos became widely used teaching stories. [late 1200s-early 1300s]

Yôdô

Yôdô was the fifth abbess of Tôkei-ji and a former princess. She was a Dharma poet, and for the Wesak festivals composed many verses which became used as teaching verses and koans for generations of nuns following her. One of her poems reads: « Decorate the heart of the beholder, / For the Buddha of the flower hall / Is nowhere else. » [1300s-1400s?]

Shozen

She was a disciple of Keizan and Sonin’s mother, but remained a householder with considerable money and power. She donated land to the temple. Keizan said the sangha would honor her forever in an annual ceremony [early 1300s?]

Mokufu Sonin

She was a disciple of Keizan and the daughter of Shozen. She was ordained in 1319. (Her husband was ordained a few years later as Myojo.) She and her husband gave a great deal of land to Keizan and invited him to found Yoko-ji there after dismantling the family home to allow this. She was the first abbot of Entsu’in, an important convent.. Keizan called her the reincarnation of his grandmother and said that he and she were inseparable. [early 1300s]

Ekyu

She was Keizan’s disciple and the first Japanese woman to receive full Soto Dharma transmission. [early 1300s]

Myosho Enkan

She was Keizan’s cousin and became abbot of Entsu’in after Sonin, and later abbot of Ho-o-ji, a convent. [early 1300s]

Soitsu

She was an heir of Gasan and had female heirs of her own.. [mid 1300s]

Shotaku

A devout nun for many years, she became the third teacher of Tokei-ji and fended off a rape using her spiritual power, by turning a roll of paper into a sword. [1300s]

Bunchi Jo

An imperial priestess who became a Zen abbot at a time of significant political change; she was renowned for painting and poetry. [1619-1697]

Eshun

She was the sister of Ryoan Emyo. Her brother refused to ordain her or sponsor her because she was beautiful and he believed she would be a sexual temptation to the monks. So she shaved her head and scarred her face with hot pokers. There is a memorial statue to her at which people make offerings in Saiko-ji at Odawara. [1600s-1700s]

Ryonen Gensho

She became a monk at 26, leaving behind her husband and children. She entered a Rinzai training monastery (Hokyo-ji) but was denied ordination by two masters because her beauty would distract the monks. She burned her face with a poker and was then ordained by Haku-o. He certified her enlightenment and she became abbot of Renjo-in and a respected poet. [1646-1711]

Teijitsu

She was head of Hakuju-an, a women’s temple now next to Eihei-ji where Soto nuns stay (because they are no longer allowed to stay at Eihei-ji). This was a time of increasingly strict prohibitions on women in social and political life, and female monastics were given less and less independence. She and Teishin are some of the last women of the period whose names are known. She was probably a disciple of Menzan Zuiho.. [1700s]

Satsu

She was a disciple of Hakuin from the age of 16 to 23. She continually engaged him in Dharma combat. After her enlightenment experience, he told her to get married in order to understand how to bring Zen into the practice of daily life. She became his Dharma heir and was highly respected. [1700s]

Ohashi

She became a prostitute as a teenager in order to support her family after her father lost his work. Despairing this fate, she was advised by Hakuin to ‘consider who does this work.’ She attained awakening after fainting in fright when a bolt of lightning struck nearby. Hakuin certified her awakening and sometime later, after more work as prostitute, she became a nun. [1700s]

Mizuno Jorin

Hori Mitsujo

Yamaguchi Kokan

Ando Dokai

These four nuns established the Aichi-ken Soto-shu Niso Gakurin (commonly called Nigakurin) on May 8, 1903, nine months after the Soto-shu regulations prohibiting women’s education facilities were lifted. They were key figures in re-opening Soto to women after centuries of increasing limitations. All four spent their entire adult lives striving to create monasteries for women at a time of tremendous political and social upheaval. [late 1800s-1900s]

Kendo Kojima

She was born in 1898 and wanted to be a nun from a very young age. Kojima eventually became the first leader of the Pan-Japanese Buddhist Nun Association, a group supported by Koho Zenji when he was the abbot of Soji-ji. She was executive director of the Japanese Federation of Buddhist Women and the only Japanese of either gender at the 3rd and 4th International Buddhist conferences.

In the middle of the century, in spite of the war, Kojima led a fight to equalize the treatment of women within the Soto-shu. Only a fraction of the money spent on the training of men was available to women, and the women’s training was strictly limited in terms of education and practice. Their transmissions were not officially recognized, they couldn’t transmit their own disciples, and weren’t allowed to participate equally in the Soto-shu administration. Paula Robinson says of Kojima, « She was notorious for speaking out at official sect meetings, frequently the only nun among many powerful male leaders of the sect. She pounded her fist and spoke with conviction. » On Sept. 29, 1952, she received an award of excellence from the Soto-shu.

Something akin to true equality was finally offered in 1989 when nuns were given the right to be named Zen Masters and temple heads. Kojima died a few years ago, in her 90s.

Yoshida Eshun

An heir of Hashimoto-roshi and abbess of Kaizen-ji Temple in Nagoya. She taught robe, rhakusu and o-kesa sewing and brought this craft to the United States in the early 1970s. [1907-1982]

The Western Ancestors

Ruth Fuller Sasaki

One of the first Westerners of either gender to train in Japan. She studied with D. T. Suzuki, was an important translator of work into English, and restored Ryosen-an (a sub-temple of Daitoku-ji) with her own money and served there as priest, the first American woman ever to do so. [1893-1967]

Soshin O’Halloran

Maura O’Halloran was born in Boston in 1955. In 1979, she followed her interest in meditation to Japan. She knew very little of Buddhism or Zen (or Japan) when she arrived, but was ordained and given the Dharma name Soshin, which means both « great enlightenment » and « simple mind. » She trained for three years and in 1982 received transmission. One of her hopes was to start a Zen Center in Ireland. Six months later, at the age of 27, she was killed in a bus accident in Bangkok. There is now a statue of Soshin as an incarnation of Kanzeon at Kannon-ji. [1955-1982]

Maurine Myo-on Stuart

A student of Yasutani and Soen Nakagawa, ordained by Eido Shimano of Dai-bosatsu, Stuart was leader of the Cambridge Buddhist Association for eleven years, and was named a roshi by Soen Nakagawa. She had many students of her own.

Gesshin Cheney

Born in Germany, Gesshin studied in the U. S. under Sasaki Roshi and Hirata Roshi. She founded the International Zen Institute of America and Europe and eventually received transmission as a dharma heir in the Vietnamese Rinzai Zen line of Thich Man Giac. Her complete name was Gesshin Myoko Prabhasa Dharma.

Jiyu Kennett

Kennett was the first western woman (and one of the first westerners ever) to train at Soji-ji. She was ordained and transmitted in both Malaysia and Japan, and given inka by Keido Chisan (Koho Zenji), the Abbot of Soji-ji. She came to the United States in the 1960s and eventually founded Shasta Abbey, a traditional training monastery for both men and women. She interpreted and translated Dogen’s work and the Soto liturgy into English and has many Dharma heirs who continue to teach. She is honored as the founder of Dharma Rain Zen Center, among others. [1924-1996]

————————————————————————

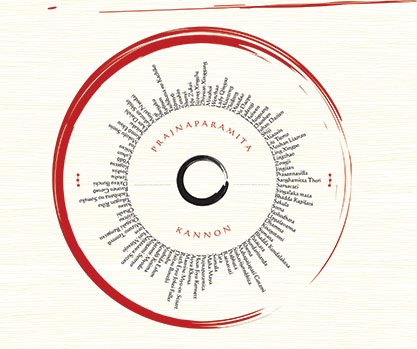

The Recitation

We offer the merits of this recitation of _________ to:

Prajna Paramita Dai-osho

Maha Maya Dai-osho

Ratna-vati Dai-osho

Shri-mala Dai-osho

Maha Paja-pati Dai-osho

Khe-ma Dai-osho

Pata-cara Dai-osho

Ut-tama Dai-osho

Bhad-da Dai-osho

Dhamma-dinna Dai-osho

Kisagotami Dai-osho

Dhamma Dai-osho

Suk-ka Dai-osho

Ub-biri Dai-osho

Uppalavanna Dai-osho

Su-mana Dai-osho

Pun-nika Dai-osho

Su-bha Dai-osho

Ut-palavarna Dai-osho

Zong Chi Dai-osho (Tsung-ch’ih)

Shiji Dai-osho (Shih-chi)

Ling Xing-po Dai-osho (Ling Hsing-p’o)

Lingzhao Dai-osho (Ling-chao)

Liu Tiemo Dai-osho

Moshan Liaoran Dai-osho (Mo-shan Liao-jan)

Miaoxin Dai-osho (Miao-hsin)

Wujin Cang Dai-osho (Wu-chin-tsang)

Daoshen Dai-osho (Tao-shen)

Huiguang Dai-osho (Hui-kuang)

Gongshi Daoren Dai-osho (K’ung-shih Tao-jen)

Yu Daopo Dai-osho (Yu Tao-p’o)

Huiwen Dai-osho (Hui-wen)

Fadeng Dai-osho (Fa-teng)

Wenzhao Dai-osho (Wen-chao)

Miaodao Dai-osho (Miao-tao)

Zenshin Dai-osho

Zenzô Dai-osho

E-zen Dai-osho

Kômyô Dai-osho

Eshin Dai-osho

Shôgaku Dai-osho

Ryônen Dai-osho

E-gi Dai-osho

Jô-a Dai-osho

Mugai Nyodai Dai-osho

E-kan Dai-osho

En’i Dai-osho

Shidô Dai-osho

Yôdô Dai-osho

Shô-zen Dai-osho

Mokufu Sonin Dai-osho

Ekyû Dai-osho

Myoshô Enkan Dai-osho

Sôitsu Dai-osho

Shôtaku Dai-osho

Bunchi Jo Dai-osho

E-shun Dai-osho

Ryonen Gensho Dai-osho

Tei-jitsu Dai-osho

Satsu Dai-osho

Ohashi Dai-osho

Jôrin Dai-osho

Mitsu-jô Dai-osho

Ko-kan Dai-osho

Dôkai Dai-osho

Sozen Dai-osho

Kendo Dai-osho

Eshun Dai-osho

Sasaki Dai-osho

Soshin Dai-osho

Myo-on Dai-osho

Gesshin Dai-osho

Houn Ji-yu Dai-osho

May we live our lives in such a way that we honor all women of the dharma, and all those beings, women and men, known and unknown, who have given their lives for the benefit of our present practice. May the merit of this awaken compassion in our hearts, save all beings in the three worlds, and make the four wisdoms perfect together with all living things. May this sangha prosper, and all misfortune cease.